Medical Journals Are Corrupt and the Research Is Mostly Junk

Most of what your doctor practices is based on fraud.

Even the top medical journals are little more than industry mouthpieces, churning out mostly junk. Believing otherwise would be like trusting cigarette ads from the 1950s.

You’re better off flipping a coin than blindly trusting what’s published in medical journals—and frankly, that’s unfair to the coin. The coin isn’t taking bribes from pharmaceutical companies.

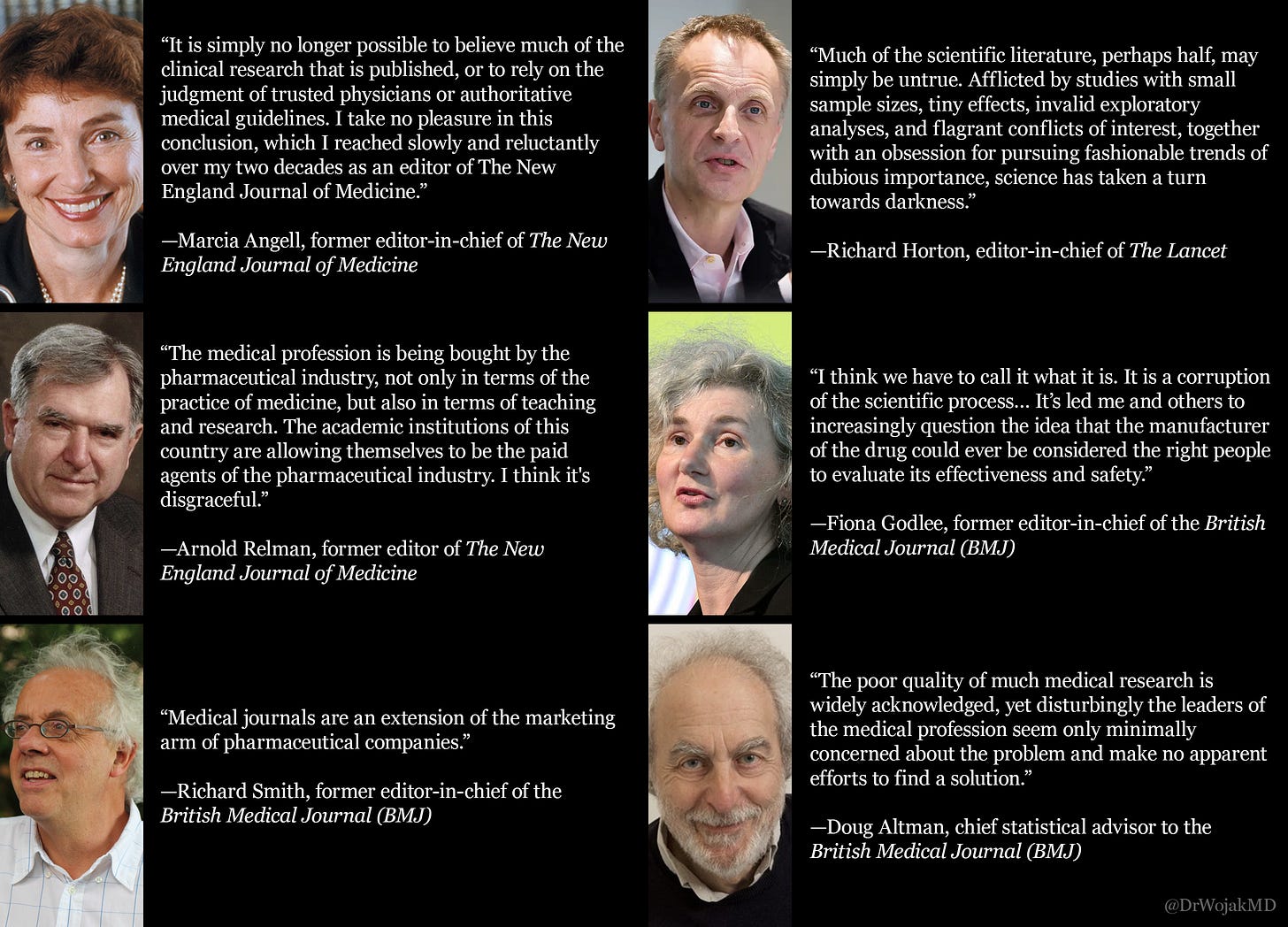

For the credential-worshipping midwits and institutional bootlickers, even editors of the world’s most prestigious journals admit how thoroughly corrupt and dishonest the medical publishing industry has become.

This is a long-ish piece—feel free to skip around using the contents list below:

Most of the Published Research Is Junk

If research can’t be reproduced, it isn’t science—it’s storytelling. Most of academia suffers from a reproducibility crisis (where follow-up studies fail to confirm the original results), but in medicine, fake science doesn’t just mislead—it kills.

Millions of studies flood the literature each year—including over 10,000 retractions in 2023 alone. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Most bad research isn’t retracted. It just lingers—polluting the knowledge base and misinforming generations of doctors, policymakers, and patients.

The Replication Crisis

Just how bad is the replication crisis?

Ioannidis (2005) examined 45 blockbuster clinical studies—the kind published in elite journals and cited over a thousand times. Only 20 (44%) were later replicated; the rest were either contradicted, overstated, or never tested again—meaning doctors routinely base treatments on dubious, unverified research.

Prinz et al. (2011) evaluated 67 preclinical drug studies. Only 14 (21%) were reproducible. These are the very studies used to greenlight billion-dollar drug trials.

Begley and Ellis (2012) tried to replicate 53 cancer studies. They succeeded with just 6 of them. That’s 11%.

Boekel et al. (2015) assessed 17 neuroimaging studies. Only 1 replicated. That’s 6%.

The problem isn’t limited to obscure journals. This is the mainstream medical literature—the very foundation of so-called “evidence-based medicine.” And most of it is irreproducible or unverified.

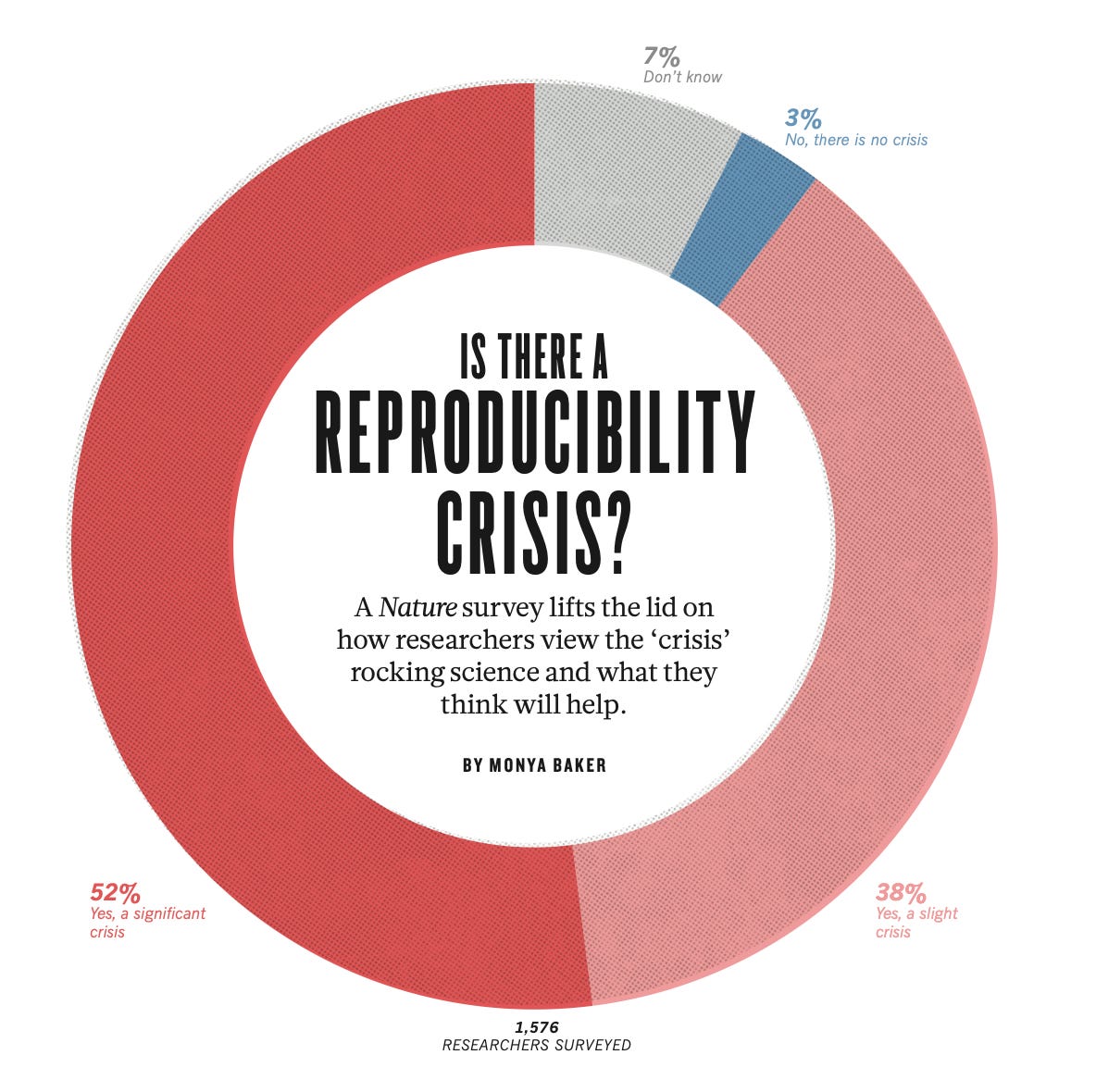

The reproducibility crisis is so severe that 90% of researchers acknowledge it—and the rest are either lying or deeply delusional.

Conflicts of Interest at Every Level

Medical Journals

The revenue of medical journals depends heavily pharmaceutical companies, mainly through advertising and reprint purchases—arrangements that resemble bribes more than legitimate business transactions.

In typical advertising, the goal is to inform potential customers about a product. But in medical journals, pharmaceutical ads serve as financial incentives designed to influence editorial decisions. Similarly, reprints (purchases of specific articles by drug companies) are essentially bribes that influence which studies get published. Without lucrative reprint orders from pharmaceutical companies, medical journals would struggle to stay afloat.

When drug companies want their studies published, they often offer substantial reprint orders if the paper is accepted. A favorable study in a high-impact journal is much more valuable than an ad—it becomes a tool doctors use to justify pushing drugs on patients. Doctors serve as the primary sales force for the pharmaceutical industry, and the junk published in these journals is their ammunition.

In May 2003, BMJ’s cover depicted doctors as pigs feasting at a banquet, being served by lizard drug reps. This spot-on portrayal struck a nerve, prompting pharmaceutical companies to retaliate by threatening to pull £75,000 in advertising. Similarly, the Annals of Internal Medicine lost an estimated $1-1.5 million in ad revenue after publishing a study critical of industry advertisements.

As for reprints, even The Lancet—Europe’s most prestigious medical journal—admitted that 41% of its revenue comes from selling reprints. If The Lancet is willing to admit this, it’s safe to assume that the situation is even worse at top US journals, which refuse to disclose their numbers.

The financial stakes are staggering. A 2005 report revealed that publishing a favorable paper could be worth up to £200 million to a pharmaceutical company, with a share of that money flowing into the pockets of doctors who promote the company’s products.

The corruption spans the entire gamut of medical journals—from the most prestigious to niche specialty publications. Transplantation and Dialysis rejected an editorial critical of a drug after three peer reviews—not due to scientific merit, but because its marketing department overruled the editors. Smaller specialty journals are often even more entangled with pharma, regularly publishing industry-sponsored symposia filled with brand names, and crafted to sell products. In one infamous case, Merck created an entire journal itself, packed with ads and favorable articles, dressed up to look like independent research.

Journal Editors

A 2017 study published in the BMJ found that over half (50.6%) of editors at the world’s most influential medical journals were receiving money directly from pharmaceutical and medical device companies—sometimes tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In 2014 alone, the average editor received $27,564 in personal payments, plus additional “research” funds—often a loose label for lavish, industry-sponsored perks and travel. At the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 19 editors were paid an average of $475,072 each, along with another $119,407 in so-called research payments.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials of drugs and other medical treatments are more propaganda than science. Unlike real science, they typically can’t be independently replicated, debated, or scrutinized—because companies control the data and bury anything that doesn’t serve their interests.

The situation is worse than most realize. A review of trial protocols found that in half of the cases, sponsors (i.e. pharmaceutical companies) had the power to block publication. In most others, they could erect legal or logistical barriers. At US medical schools, industry-sponsored research routinely violates editorial norms, including access to raw data and the right to publish findings.

A 2005 survey revealed that 80% of schools would accept contracts giving sponsors data ownership, and 50% would allow sponsors to ghostwrite the study. Even after signing, 82% of institutions encountered conflicts with sponsors. In one case, a company withheld final payment because it didn’t like the study results. Contracts are typically kept secret, making it likely that the true extent of corruption is underestimated. Nonetheless, 69% of administrators admitted that funding pressures often forced them to accept unethical terms. The result is an academic research culture almost wholly corrupted by industry.

Under current rules, sponsors typically own the entire dataset, control who can access it, and allow investigators to view only selected summaries—usually on the company’s premises.

Industry funding now dominates clinical research. In the US, it rose from 32% in 1980 to 62% by 2000. Academic medical centers receive a shrinking portion of these funds—falling from 63% in 1994 to 26% in 2004—with private contract research organizations (CROs) taking over. Many CROs are openly involved in marketing, further blurring the line between research and sales.

To stay competitive, universities court industry dollars, offering access to patients and clinical staff. Doctors are reduced to recruiters, offering up their patients in exchange for perks and publications. In some cases, doctors receive up to $42,000 per patient enrolled.

Peer Reviewers

Between 2020–2022, over half of peer reviewers for JAMA, New England Journal of Medicine, BMJ, and The Lancet took money from drug and device companies—$1.06 billion total.

58.9% received industry payments

54% took general payments (like gifts, speaking fees, etc.)

31.8% accepted research funding

The median research payment? $153,173.

These aren’t fringe journals. These are the so-called gold standard of medical publishing. And the people deciding what gets published are bankrolled by the very industry they’re supposed to keep in check.

Peer reviewers don’t even have to disclose their conflicts—unlike editors and authors. Journals will keep their names and ties hidden from the public.

Biases

Bias Toward Positive Results

One of the most pervasive biases in medical research is the preference for positive findings. Studies that support a treatment or intervention are far more likely to be published, cited, and taken seriously—regardless of their quality.

This bias shows up across the entire research pipeline: from researchers designing studies to journals deciding what gets published. A 2010 study found that papers with positive results were accepted 97.3% of the time, while those with negative findings were accepted only 80% of the time.

The pharmaceutical industry exploits this bias to its full advantage. Drug companies are far more likely to publish studies with favorable outcomes and bury the rest. In one analysis of antidepressant trials submitted to the FDA, 94% of the positive studies were published—but only 8% of the negative ones. If you relied solely on the published literature, it would appear that antidepressants are overwhelmingly effective. In reality, only 51% of all trials showed any benefit at all.

This is the file-drawer problem in action: negative or inconclusive results are quietly shelved, while positive ones flood the journals. It’s not just misleading—it’s deception by omission, and it systematically distorts our entire understanding of medical science.

Publish-or-Perish Culture

Academia rewards volume more than quality. Researchers are pressured to publish constantly or risk losing funding, promotions, or their careers.

Instead of pursuing careful, meaningful research, academics are pushed to crank out papers that are more likely to get published.

The result is a flood of low-quality studies—designed to serve industry interests, pass peer review, and pad résumés. Lots of junk science makes it into journals, as long as it checks the right boxes.

Bias in Study Design

Bias often begins before the research even starts—during the design phase. Researchers craft studies that are more likely to confirm their own hypotheses, introducing confirmation bias from the outset. Even without bad intentions, decisions about what to measure, how to measure it, and how to frame questions can all tilt results in a particular direction. Combined with the pressure to publish and a lack of transparency, these structural biases lay the groundwork for flawed, untrustworthy research.

Fraud and Other Misconduct

Fraud

The problem isn’t just bias or conflicts of interest—it’s widespread, deliberate fraud. The true extent of scientific misconduct is likely much worse than the following numbers suggest, because most researchers are unlikely to admit to fraud—even anonymously.

A survey of 3,247 NIH-funded US scientists found that 33% admitted to questionable research practices in just the past three years, including:

16% who altered study design, methodology, or results due to funding pressure

15% who dropped inconvenient data points

14% who used inappropriate or inadequate research designs

In a broader review of 21 surveys on research misconduct:

Up to 5% of scientists admitted to falsifying or fabricating data

Up to 33% had personal knowledge of colleagues who falsified data, with up to 72% aware of other questionable practices

Up to 34% admitted to other forms of misconduct

Another survey revealed that 81% of biomedical research trainees were willing to omit or fabricate data to secure a grant or publication.

Ghostwriting

Ghostwriting is a deeply ingrained practice in the world of medical research, wherein pharmaceutical companies hire writers to create research papers that are then published under the names of prominent academics or researchers.

A study examining industry-funded trials found that 75% had ghost authors—and that number jumped to 91% when counting researchers who should’ve been listed as authors but were only mentioned in the acknowledgments.

P-hacking

In the world of medical research, p-hacking refers to the manipulation of statistical data in order to achieve a result that is statistically significant (a p-value less than 0.05) but may not actually reflect the true nature of the data. This practice is rampant in clinical trials, where researchers are under pressure to produce favorable results to satisfy funding sources or meet publication goals.

P-hacking typically involves data dredging, which means looking for patterns in data that were not part of the original hypothesis, or selective reporting, where researchers focus only on certain outcomes that appear to support their conclusions. This leads to false positives—results that suggest an effect where none exists—and it contributes to the growing body of scientific literature that is not just misleading but downright fraudulent.

Censorship

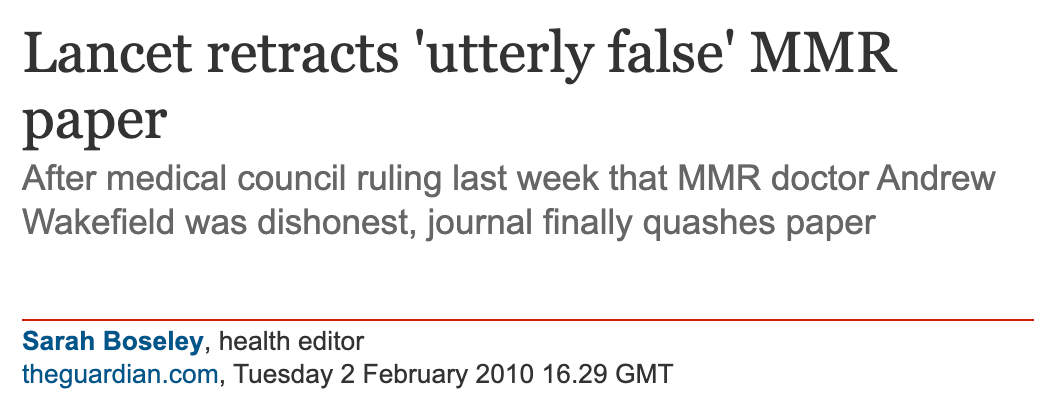

Censorship in medical publishing is not just a matter of rejected papers—it often takes the form of targeted suppression, retraction, and professional destruction for those who challenge prevailing industry narratives. Two revealing examples are Dr. Andrew Wakefield and Dr. Paul Thomas, both of whom had peer-reviewed studies retracted and saw their careers subsequently ruined.

In 1998, The Lancet published a paper coauthored by Dr. Andrew Wakefield suggesting a possible link between the MMR vaccine and gastrointestinal issues in autistic children. The study was cautious in its conclusions and openly called for more research, but the reaction was brutal. Under intense institutional pressure, The Lancet retracted the paper, and Wakefield was stripped of his medical license. Whether one agrees with the study’s interpretation or not, the response was not about scientific discourse—it was about enforcing the limits of acceptable inquiry.

A similar fate befell Dr. Paul Thomas, who in 2020 published a peer-reviewed study comparing health outcomes in vaccinated and unvaccinated children in his own practice. The data showed that unvaccinated children experienced fewer chronic conditions. The study was later retracted without serious scientific refutation, and Dr. Thomas had his medical license suspended. The punishment didn’t stem from fraud or methodological flaws—it came from presenting findings that challenged powerful interests.

This kind of censorship isn’t limited to high-profile cases. Entire categories of research that question pharmaceutical products, vaccine policy, or dominant public health narratives are routinely excluded from publication. Journals—deeply entangled with industry funding and reputational concerns—act as ideological gatekeepers. Studies with inconvenient findings are quietly filtered out, while industry-friendly papers are ushered through the process.

Peer Review

The peer review process in academic journals is a joke. It’s riddled with flaws and biases that allow subpar research to pass through unchecked—while suppressing work that challenges industry narratives. Far from being a rigorous quality control mechanism, peer review is a broken system that protects prestige, profit, and orthodoxy over truth and accuracy.

Many reviewers barely read the papers. Some don’t understand the methods. Others are selected because they’re sympathetic to the authors or aligned with the desired conclusions. The result is a gatekeeping process that legitimizes junk science and buries inconvenient findings.

Reviewers Don’t Agree

Reviewers frequently disagree with one another, often to the point where their assessments are no better than random chance. A meta-analysis of inter-rater agreement found that peer reviewers tend to have a low level of agreement when evaluating the same research. If reviewers can’t even agree among themselves on what constitutes good research, how can we trust their evaluations to be accurate or meaningful?

Peer Review Fails to Catch Obvious Nonsense

Prestigious journals have repeatedly published fake or blatantly nonsensical studies, revealing just how broken the peer review process truly is. In 2009, the BMJ published a paper on a fictional condition called “cello scrotum.” The authors submitted it as a joke, expecting someone to catch it. No one did.

In 2013, a journalist sent a deliberately bogus paper—riddled with basic chemistry errors—to over 300 journals. More than half accepted it for publication.

Peer Review Fails to Catch Basic Errors

A significant criticism of peer review is that it often fails to catch even basic errors in submitted papers. Numerous studies have demonstrated that reviewers frequently miss glaring mistakes, and this failure calls into question the reliability of the process. One notorious experiment by Fiona Godlee, editor of the BMJ, involved inserting eight deliberate errors into a paper about to be published in the journal. The paper was then sent to 420 reviewers. Of those, only 53% responded, and the average number of errors identified was just two. Astonishingly, 35% of reviewers failed to spot any errors at all.

In another study conducted by Godlee in 2008, nine major and five minor errors were inserted into a paper and sent to 607 reviewers. Despite the glaring mistakes, the error detection rate remained dismal.

Academics Don’t Understand Statistics

A further issue with peer review is the lack of statistical literacy among academics. Despite their credentials, many researchers—including those tasked with reviewing papers—do not fully understand key statistical concepts like p-values, confidence intervals, and t-tests. This lack of understanding compromises their ability to assess the validity of research findings.

For instance, in a 2015 study, 89% of epidemiologists failed to properly interpret a statistical result about a cancer intervention when the p-value exceeded 0.05, even though this result was statistically significant. Similarly, a 2016 study found that 84% of statisticians failed to properly assess a comparison between two drug treatments. If even experts in the field cannot correctly interpret basic statistical results, how can we expect peer reviewers—who are often selected based on their expertise in a narrow subfield—to effectively evaluate the statistical soundness of research?

Biases of Peer Reviewers

Peer reviewers tend to favor papers that align with their own perspectives or prior beliefs. This bias leads to the reinforcement of established ideas and the suppression of novel or controversial research.

In a 1977 study, researchers found that peer reviewers rated papers reporting positive results in line with their own beliefs as higher quality, while papers that contradicted their views were rated more negatively. Similarly, a 1993 study found that scientists were more likely to accept papers that agreed with their prior beliefs. Confirmation bias is rampant in the peer review process. Instead of fostering open-minded evaluation, peer review just reinforces the status quo.

Impact Factor

Journal prestige is built on a very manipulable metric—impact factor, which is a measure of how often a journal’s papers are cited. Pharmaceutical companies exploit this metric by orchestrating ghostwritten, secondary publications that cite flawed trial results, boosting both their own marketing and the journal’s prestige.

Take the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), for example. Trials of Pfizer’s voriconazole were published in the NEJM with misleading conclusions, but these flawed studies were cited hundreds of times in other papers, many likely ghostwritten by the company. This citation network artificially inflated the journal’s impact factor, boosting its reputation while spreading corporate propaganda.

By publishing and promoting these biased trials, journals profit from selling reprints, while pharma companies gain more exposure for their products. Impact factor can reflect industry influence more than scientific merit.

What Real Peer Review Looks Like

Real peer review isn’t a behind-the-scenes approval process run by nameless gatekeepers in industry-captured journals.

Real peer review happens out in the open—on platforms like Substack, X, independent blogs, and open-access journals—where anyone can read, critique, and engage with the material directly. No anonymous panels or backroom deals.

More researchers are publishing in open-access and preprint journals, where findings are freely available and subject to public scrutiny. There’s also growing pressure on institutions to publish all results, including negative ones—not just the ones that serve commercial interests.

Unlike the corrupt medical journals propped up by pharmaceutical money, real peer review is decentralized and transparent. It thrives where ideas rise or fall based on merit, not brand-name journals or insider networks.

That’s why the medical establishment fights so hard to control the internet and censor dissent—like we saw during the fake covid pandemic, when too many started thinking for themselves. If free discourse is allowed, their grip on the narrative— propped up by the illusion of journal prestige—starts to slip.

Final Thoughts

Anyone still appealing to journal prestige as evidence of scientific integrity is either hopelessly gullible or complicit in the corruption.

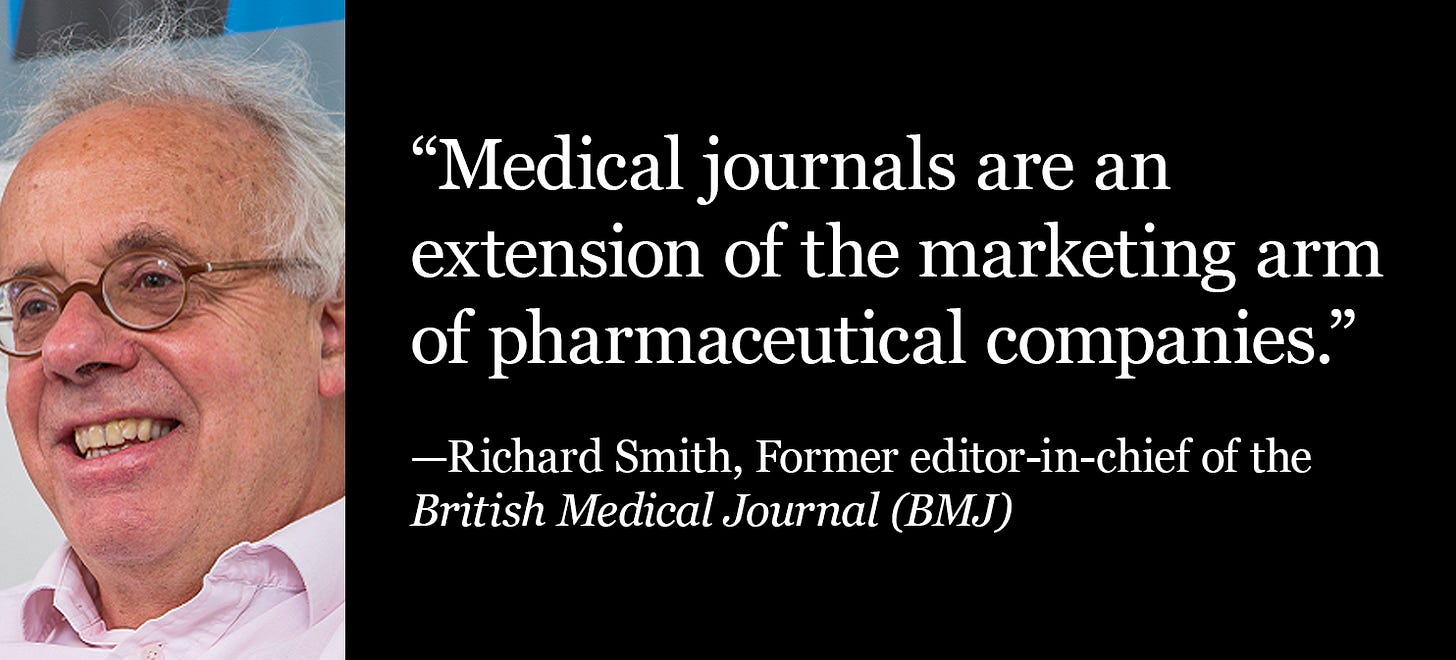

Arnold Relman, former editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, warned us decades ago:

“The medical profession is being bought by the pharmaceutical industry—not only in terms of the practice of medicine, but also in terms of teaching and research. The academic institutions of this country are allowing themselves to be the paid agents of the pharmaceutical industry. I think it’s disgraceful.”

He was right. The corruption isn’t peripheral—it’s foundational. Journals, editors, researchers, and institutions have all been captured. What passes as “evidence-based medicine” is often just commercially-driven dogma dressed up in scientific language.

We must stop treating journal publication as a proxy for truth. Research should be judged on its own merits—openly, transparently, and case by case. That shift is already happening in decentralized spaces: Substack, X, independent blogs, and open-access platforms where ideas are dissected in public.

The stragglers still clinging to the old illusions are stalling the collapse of a rotting system.

As a board-certified subspecialist in practice for over 30 years, I have witnessed the corrosive effects of pharma’s influence over clinical medicine. It is as bad as Dr. Wojak says.

I wrote an article back in December on this very subject. People are totally unaware of how corrupt and bereft of scientific integrity the medical industry really is. You cannot trust a word they say.

See my article The Medical Profession is a Cesspool of Fraud, greed, Corruption and Bad Science.

https://stephenmcmurray.substack.com/p/the-medical-profession-is-a-cesspool